What Is MoCD Type A?

Molybdenum cofactor deficiency (MoCD) Type A is a rare genetic disease that can appear shortly after birth.1,2 Children with MoCD Type A do not have symptoms at birth. But, within a few hours to a few days (sometimes longer), they often have trouble feeding and seizures that don't improve with treatment. These seizures are also called intractable seizures.3

Early diagnosis is critical—MoCD Type A is devastating and progresses rapidly.1,3,4

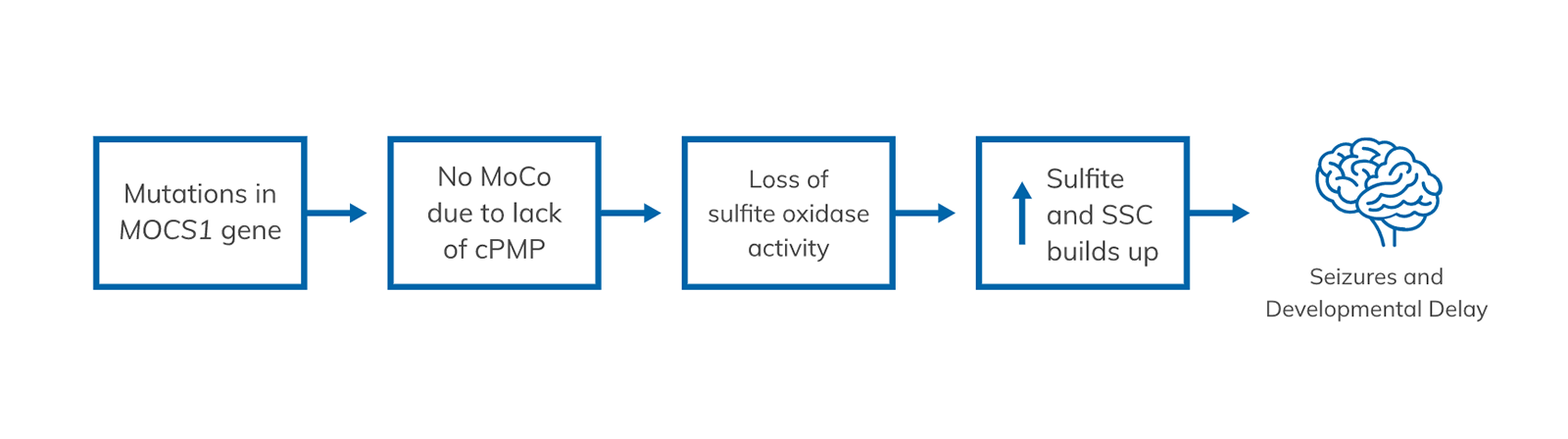

MoCD Type A is the result of a change in a gene called MOCS1. This change prevents the body from producing a compound called cPMP (cyclic pyranopterin monophosphate) and other compounds, including MoCo (molybdenum cofactor). Without MoCo, an enzyme called sulfite oxidase doesn't function, and toxic levels of sulfite and SSC (S-sulfocysteine) build up in the body, and in particular a child's developing brain. It is the build-up of these compounds that leads to seizures, severe brain abnormalities, and other features of MoCD.1 This lack of MoCo is what leads to high sulfite and S-sulfocysteine (SSC) levels and, ultimately, brain abnormalities and severe developmental delays in your child.1,3

Sulfite and SSC are substances that can be highly toxic when they build up in the body, especially in the brain.3 It is believed that too much buildup causes seizures, severe brain abnormalities, and other features of MoCD.1,3

In a child with MoCD Type A1,3

Traditionally, care has been limited to managing the symptoms of the disease.4

MoCD Type A progresses rapidly.1,3,4 Children with MoCD Type A who survive beyond the first few months usually experience3:

- Irreversible damage to the brain

- Severe developmental delays

- Brain abnormalities

There are 3 types of MoCD1:

- Type A (the most common)

- Type B

- Type C

Unfortunately, the outlook is poor for all 3 types. Most children with MoCD survive just 3 years, those with MoCD Type A survive just 4 years without intervention.1,5

MoCD Type A progresses rapidly.1 That's why it's so important to diagnose it quickly.

Diagnosing any type of MoCD, including Type A, can be very challenging. This can be for many reasons.

- MoCD is very rare, and the symptoms are the same as for other, more common conditions. Because of that, doctors may think the symptoms are due to injury at birth, infections, or other common causes6

- The tests to figure out what's causing the symptoms may or may not include the specific ones needed to help confirm or rule out MoCD7

With MoCD, the most common symptom babies experience is intractable seizures. Other symptoms include1,8,9:

- Brain abnormalities/malfunction

- Feeding difficulties

- Exaggerated startle reactions

- High-pitched cries

- Increased/decreased muscle tone

If your child has any of these symptoms, don't forget to ask your doctor if they've considered MoCD.

Diagnosing MoCD Type A usually happens in 2 steps1:

- Urine or blood test (also called a biochemical test); the results of this test, along with your child’s symptoms, are enough to confirm a diagnosis of MoCD1

- However, a genetic test is the only way to tell the difference between MoCD Type A, MoCD Type B, and MoCD Type C1,2

- Urine tests

If your child has a seizure, ask about a urine test to help rule out MoCD right away. It can check for high levels of sulfite or a substance called S-sulfocysteine (SSC).1 It is believed that high sulfite and SSC levels cause the seizures, severe brain abnormalities, and other features of MoCD.1,3 The result of this test, along with your child’s symptoms, is enough to confirm a diagnosis of MoCD. - Genetic tests

A genetic test identifies changes and mutations in genes. It is the only way to confirm which type of MoCD your child may have–Type A, Type B, or Type C.1 For MoCD Type A, it tests for mutations in the MOCS1 gene.1 Unfortunately, results for genetic tests can take weeks.10 So, it’s important that genetic testing isn't the only diagnostic tool used.

A fast diagnosis is very important with MoCD Type A. Talk to your healthcare provider right away about biochemical and genetic tests that can confirm a diagnosis.1

NULIBRY has been shown to improve survival for children with MoCD Type A.5 For the first time, children diagnosed with MoCD Type A have a fighting chance.

FDA=Food and Drug Administration.

References:

- Mechler K et al. Genet Med. 2015;17(12):965-970.

- Veldman A et al. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):e1249-e1254.

- National Institutes of Health. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/molybdenum-cofactor-deficiency.

- Durmaz MS et al. Radiol Case Rep. 2018;13(3):592-595.

- NULIBRY [prescribing information] https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=736aeea3-f206-454d-95d0-fd30964e8aab.

- Panayiotopoulos CP. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2599/?report=printable.

- Baylor College of Medicine. https://www.bcm.edu/research/medical-genetics-labs/test_detail.cfm?testcode=4400.

- Schwahn BC et al. Lancet. 2015;386(10007):1955-1963.

- Hitzert MM et al. Pediatrics. 2012;130(4):e1005-e1010.

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. https://www.chop.edu/treatments/genetic-testing.